Image Loading

By Catherine Despont

We are bombarded with images, and as a result we spend very little time with them. They flash by and we expect them to tell their story instantly. They are supposed to replace explanation, or perhaps express the unsayable. Reading text, with its attendant effort of imagination is something fewer and fewer people find time for.

We sometimes think of a painting as presenting itself all at once—that the viewer can hardly prevent her exposure once she finds herself in the same room—but John Berry’s paintings complicate and prolong this process. They invite deep looking, and often seem to morph over prolonged encounter. Things that initially feel large as in Pillar Party, can grow smaller, shapes that appear flat, develop depth, places grow near and then far again as in the red planes of Armory. Even in minute moments there is the sensation of a flicker, a blip, like a wink perhaps signaling a secret code. It feels possible that each thing may present its opposite.

Armory, 2014

Berry’s layered space and repeated symbols evoke a sense of narrative that, though visual, asks to be unpacked through verbal association as well. Sometimes the shapes are architectural (walls, bricks, tunnels, towers) sometimes natural (water, fire, wood) sometimes anthropomorphic (gangly, bulging, erect). Contrasting colors and physical proximity imbue Berry’s objects with resonance or relationship; they exist within perspectives that vacillate between the internal and external; distance is created only to collapse suddenly where it meets another plane, all of which suggests movement, direction, momentum and event. But a mountain is not only a physical place in Berry’s conception, it is also a representation of quest, “formidable yet indifferent to hubris.” A maze “suggests a looping of time, a literal and conceptual challenge.” Such descriptions evoke symbolic traditions like the Tarot where the expressive power of an image also depends on the associative skill of the viewer/reader to reveal its fullest meaning.

Visitor, 2015

In the tradition of Russian Icons, from which Berry draws heavily, Icons are often spoken of as having been “written,” in part because the Russian word for painting and writing is the same, but also because the Icons are considered to be the Gospel in paint. Such a project conveys not only the importance of accuracy in the image, but that the looking process is one in which a translation back into language occurs. One must be able to interpret the expressions of the saints, the colors of clothing, the locations of buildings and gestures of figures, in ways that enliven and expand the stories. In some sense it is not the icons that bring the stories to life, but the interpretive process of the viewer who uses the image as a tool to bring greater specificity to the Gospel.

Though such narratives may not be as explicit in Berry’s work there is often an evocative tension between title and composition. The ominous, black intrusions in Visitor read both as additive elements and as cutouts. They feel like interruptions, things that transcend or transgress the regular division of the walls. They are clearly outsiders, not guests—ghostly apparitions that pull the viewer through the foreground into a further realm maybe, or maybe into abyss? The monumental Gravedigger also plays with our sense of scale and location. The horizon line suggests the divide between above ground and below ground, but the tunneling forms also seem like instruments or infrastructure hovering in space, channels of transmission. The gravedigger is the person who officiates our physical transition between life and death; we think of him as solitary, removed by his work from the carefree experience of daily life, but also perhaps more attuned to the communication between worlds.

Gravedigger, 2015

This “reading” experience in Berry’s work also resembles the way in which the Icons unfold over time. There is an initial meeting—a first impression in which we may fall in love or find something off-putting—but there is also an encounter of different areas of time within the painting itself. An Icon may present moments of important action, like stills from movie, alongside a portrait in the foreground signaling the universal quality of its subject. Narrative aspects may be read from left to right, but there is often, importantly, a vertical access—a connection not just through time, but between worlds. We are meant to recognize and differentiate earthly space from spiritual realms and to understand/interpret the stories within the context of a spiritual perspective.

Summit, 2015

In the Icons this spiritual point of view is famously represented by reverse, or Byzantine perspective, which places the vanishing point in front of the scene, where the viewer is standing; and Berry makes subtle but effective use of this effect too. The checkered floor of Parlor and the dream-like, toe-grazing perspective of Summit seem to open away from the frame. Counter-intuitively, objects grow larger as they approach the horizon line, and shrink as they near the viewer. Reverse perspective gives the impression of moving from a small space into an expansive universe. In ideological terms it suggests worlds beyond and perhaps more important than our world. Geometrical forms present more faces than would typically be seen in linear perspective. A cube shows four faces instead of three, suggesting multiple dimensions. Clearly such symbolism feels ripe for interpretation on many levels, but the vision, or fantasy, of worlds beyond our own, or of hidden gateways, is not only a preoccupation of religion but, importantly, that of childhood too.

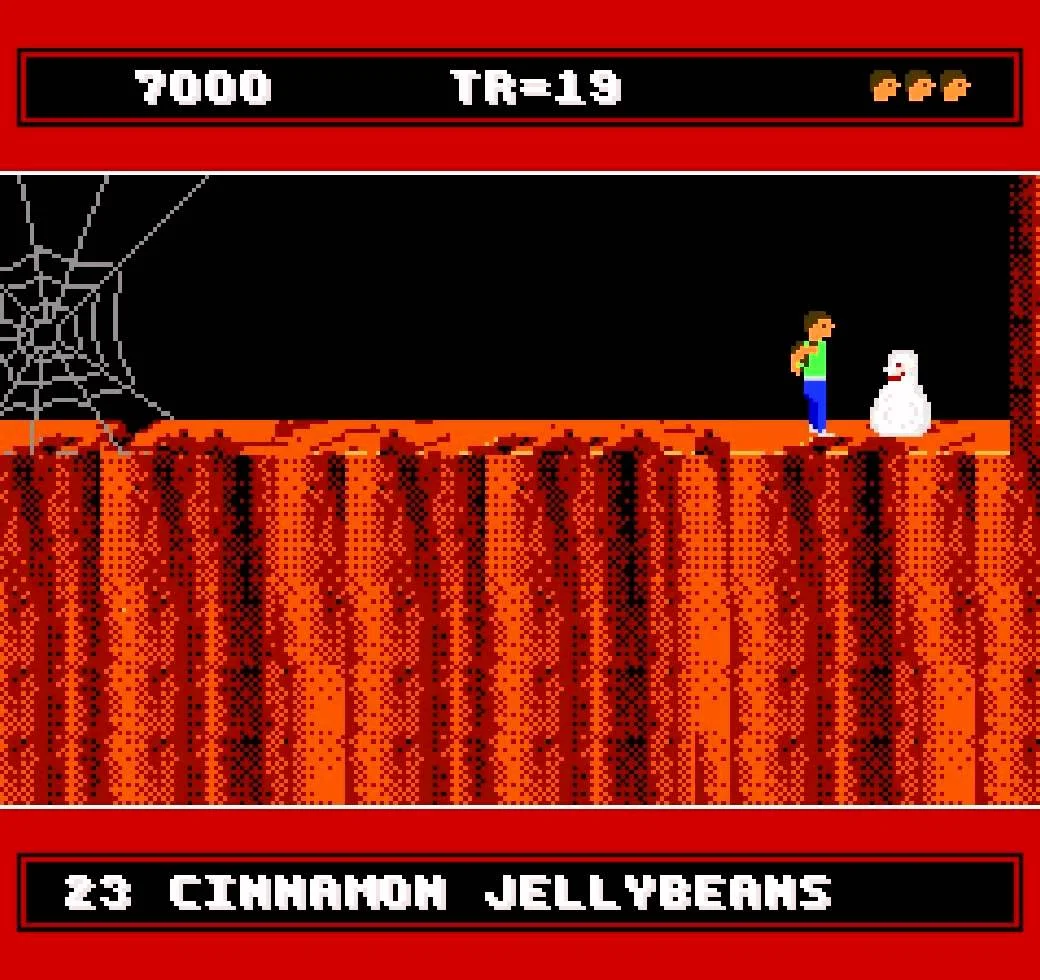

Kid Icarus, Nintendo, 1986

Childhood is perhaps the time when we are most attuned to the transformative power of small spaces. That age is imbued with premonitions of further lands—a sense of places existing beyond its own experience, like the adult world, but also the worlds of animals and under-beds, closets, attics, basements. Alice in Wonderland, The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, Time Bandits, and Never-Ending Story, and even Harry Potter all have as their point of departure a small, often dark, but rather ordinary place—respectively a rabbit hole, a wardrobe, a closet, a book and attic, a train platform. The semi-serious, mythic-heroic quality of Berry’s titles such as Bandit, Portal, Shield, Spell, Snake Pit and Trojan Wall recall this questing-space of childhood as well as that other realm that has become so associated with it—that of the video game.

A Boy and His Blob: Trouble on Blobolonia, Nintendo, 1989

Like paintings and books before it, the video game opened new spaces for the heroic quest to unfold. The limited language of their early incarnations meant that the imagery was highly abstract. The square bit rendered everything to rough blocks, and Berry’s cartoonish bricks and brightly colored platforms make direct reference to this early aesthetic. The rough and somewhat comical appearance of the video game, though slightly ironic, never prevented it from being filled with magical powers, golden treasures, and arch rivals. Does enacting these stories within the virtual realm somehow distance us from their psychic resonance? The trend in video games has been for graphics to grow more “realistic” and for story possibilities to grow more complex, and yet the question remains about whether their realism actually brings us further into a mystical realm or just deeper within the virtual one.

“Seeing landscape in perspective presupposes a major re-ordering of time as well as of space,” explains Yi Fu Tuan, in his seminal work on the human environment, Space & Place, The Perspective of Experience. “From the Renaissance onward, time in Europe was steadily losing its repetitions and cyclical character and becoming more and more directional.” This is especially true within the video game that loses its allure once it has been won. Instead of reintegrating the insights of the quest within a continuum that grounds the hero-player more deeply in the world, the commercial video game is ultimately created to fuel the desire for more games. It isn’t mythic, but consumerist. In contrast the narrative experience of paintings changes and evolves as viewers bring their own imaginative experiences to bear, imbuing repeated viewings with a cumulative understanding.

Berry’s work asks us to reconsider the resonance of the spaces we inhabit, both physical and virtual. Perhaps we think they are modern, electric, mechanical—that that they do not admit the sacredness of older dimensions. Berry re-appropriates the multi-dimensionality of the still image, the programmed landscape. He connects them to the psychological realm of childhood, and sensitizes us to the communicative nature of object, regardless of age or provenance, to be talismans of a cyclical experience that governs all life.